Captain Sam Storer was there at Bullecourt in France in 1917, and waited 60 years to write a damning account of the battle that, more than any other, provoked in the Australians the deepest contempt for their British commanders. But haunting his mind was helplessness, ghosts of a calamity from before his time, and in France 100 years ago today, tragedy repeated itself.

Captain Sam Storer was there at Bullecourt in France in 1917, and waited 60 years to write a damning account of the battle that, more than any other, provoked in the Australians the deepest contempt for their British commanders. But haunting his mind was helplessness, ghosts of a calamity from before his time, and in France 100 years ago today, tragedy repeated itself.

Sam wasn’t born when it happened. His parents never spoke of it. But he knew all about his oldest brother whom he’d never met. In 1887, Sam’s father carried the bloodied and lifeless body of 12-year-old Robert back to the family’s farm house in north west Victoria. His wife ran to the door, paused, her face ashen with angst, and she collapsed in absolute grief. Their 18-month-old son John had got too close to the threshing machine. Big brother Robert was alert to the danger, and lunged, pushing the toddler to safety. But Robert himself was consumed by the machine, killing him instantly.

Thirty years later, on the 11th of April 1917, Sam and Bert – the two youngest of 10 Storer brothers – were serving together in the 14th Australian Infantry Battalion. They readied themselves for the battle at Bullecourt. Bert was a corporal, having survived Gallipoli and Pozières. Sam was a platoon sergeant. Their captain was the revered Albert Jacka who’d already been awarded a Victoria Cross, a Military Cross, and on this day was fated to win another. (Afterwards, everyone who served with him knew he’d really earned three VC’s.) Jacka argued against the plans. He was not offered any more promotions throughout the war.

The Australians were thrown out to hang on the German barbed wire, bodies sliced apart by the spew of machine guns, all without the protection from the usual artillery barrage. You see, they were crash test dummies alongside unproven British tanks. Despite the utter failure of the new technology, the Australians miraculously took their objectives, but couldn’t hold on. They suffered over 3,300 casualties, including 1,170 taken prisoner – the largest number captured in a single engagement during the First World War.

In Sam’s book published years later, he referred to his late brother Bert, who’d heroically fallen victim to the German threshing machine, only once and not by name. Sam was still grief stricken all those years later.

“At the roll call next day, only 75 of the 800 or so men of the 14th Battalion were left alive. My brother, who was only a short distance from me during the attack, was reported missing. I was informed by his comrades that he had taken a direct hit from a shell, and was buried right up to his armpits and seriously wounded. They were trying to extricate him when the Germans entered the trench. He begged them to leave him alone and save themselves.”

Other accounts reported that Bert had taken a wound to his shoulder. As the Australians retreated from a German counter-attack, he chose to remain behind in the trench to surrender the wounded. He was not seen alive again.

His local newspaper back in country Victoria reported he was killed, when in fact he was only reported missing. They retracted the story as the large family clung to the slimmest of hopes. Seven months later, however, the prayers of their long grieving mother proved to be in vain, when Bert was finally declared dead.

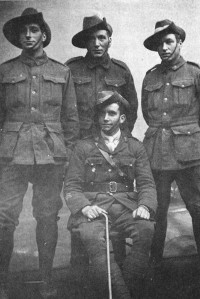

Sam continued to serve. He’s photographed here in 1918, seated in front of three cousins in France. On his right is George Torney, wearing the ribbon of a Distinguished Conduct Medal, second only to a Victoria Cross. All in the photo are cousins of mine. Bill Mawhinney, another cousin, served alongside Sam and Bert in the 14th Battalion at Bullecourt, and was taken prisoner during the attack. Sam later became mayor of Swan Hill.

The 11th of April a century ago today, is not one to be forgotten in my family.

#Bullecourt100

Fantastic Harold

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Harold i enjoyed the read, also wanted to let you know that W>G>Torney in the photo is the tallest one in the back left. It was a surprise to see my grandfather as i have not seen this photo before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Beth, I’m so pleased that you liked the story. You and I are related, and I would love to know more about your family especially your grandfather William George Torney DCM who is in this photo. Please email me on info@historyoutthere.com I look forward to chatting soon!

LikeLike

Hello Harold, thank you for showing this and your historical information. Bill Mawhinney (Marney) was my grandfather Tom Marney’s brother. I don’t have much information about my family. My father Dan (Danny) was Tom’s son. It’s fascinating and helpful with understanding my family history.

Thank you

Sarah

LikeLike